Liver Transplantation

Liver Transplantation

HERE I AM HERE THAT Site Have SQLI BUG my id : python_insta_

The information provided here is a guide, and reflects only the views of Dr Crawford

The Liver

The Liver

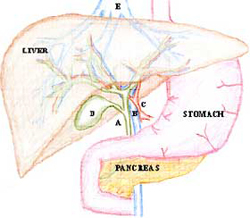

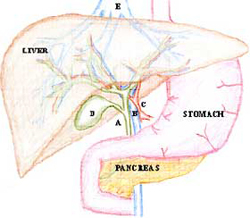

The liver is a large organ in the upper abdomen, just below the diaphragm. It is a major source of proteins for the body and processes much of the food we eat. It also secretes bile via the bile ducts into the gut. The gallbladder (D) stores bile. It is connected to the main bile duct (A) and hangs off the liver.

The liver receives blood from two sources; the portal vein (B) and the hepatic artery (C). Blood leaves the liver through hepatic veins (E) into the vena cava just below the diaphragm. The liver is divided into eight anatomical segments by the branches of its veins.

Liver Transplant

A liver transplant involves removing the entire liver and replacing it with a liver from a donor. This is long and complicated surgery, taking between 3 and 6 hours. Expert anaesthesia is required.

Who needs a liver transplant?

Who needs a liver transplant?

Patients with end-stage liver disease from any cause might be suitable for liver transplant. The vast majority have advanced cirrhosis of the liver. The process of selection for this procedure is complicated and involves many health professionals. Because donor organs are in short supply it is important that the long-term results of liver transplant are good. Therefore, patients whose life-expectancy after transplant is poor are generally not offered transplants. Patients small primary liver cancers are generally considered, but those with large cancers, or secondary cancers are not.

What tests are done?

A standard battery of tests are performed including blood tests, xrays (including CT scan), ecg and cardiac echo, bone densitometry, viral screening etc. Further specific tests are often required according to individual patient risks. The aim of the tests is to rule out cancer, or other diseases that might impact on the outcome after a liver transplant, and also to ensure fitness for the surgery itself.

How is the liver transplanted?

How is the liver transplanted?

The donor liver is a generous gift from a person who has usually died suddenly and unexpectedly. An expert team of surgeons performs an operation at the hospital where the donor has died. During this operation the liver is flushed to remove blood and stored in a preservation solution at 4 degrees. The liver is transported back to the transplant hospital in ice. The liver can survive like this for many hours but not days. Once the liver has made it to the hospital the operation begins. There are lots of drips and monitoring devices placed by the anaesthetist. A large upside down Y incision is made in the upper abdomen. The liver is mobilised off its attachments and the portal vein and hepatic artery are clamped off and cut. The inferior vena cava is clamped and the liver is removed.

The new liver is now sewn in by connecting all the blood vessels and bile duct up. It starts to function almost straight away. Drains are always placed in the abdomen to drain any blood or bile.

The post-operative course

The post-operative course

The post operative course is different for each person. All patients are admitted to Intensive Care for at least the first post operative night. The majority of patients will stay on a ventilator for the first post operative night. Patients are usually transferred to the ward on the second or third day after transplant, and quickly return to a normal diet. Patients can expect a 2-3 week stay in hospital to recover from the surgery and stabilise their medications. If complications occur they can expect to stay longer.

Immunosuppression

All patients will take medicines to control rejection for the rest of their lives. These start off as high dose until the body gets ?used to? the new liver, and are gradually tapered down to a small number of tablets. Regular blood tests are required especially early on to ensure the dose is the correct one. Some patients suffer side effects of the medicine that include; diabetes, blood pressure, kidney dysfunction, and tremors. Most of these are easily managed by the transplant team.

What are the potential complications?

The risks of complications varies between patients. In general, the sicker the patient, the higher risk. The risks are also higher if the patient has significant other illnesses.

Potential complications of liver transplant surgery include (but not limited to);

- Bile leak. Bile may leak from the join in the bile duct. If this happens it may be necessary to operate to repair it.

- Bleeding. Bleeding may occur during the surgery (requiring transfusion), or post operatively occasionally requiring a return to the operating room to control bleeding.

- Intra-abdominal collection. Fluid may accumulate near the liver (blood or bile) that can become infected and occasionally needs to be drained.

- Primary non function. This is a rare complication where the transplanted liver fails to function adequately and requires an urgent re-transplant.

- Hepatic artery thrombosis. If the artery clots in the early days after transplant, there is a risk that the liver will fail leading to a re-transplant. If the artery clots later it may be associated with bile duct problems down the track.

- Respiratory problems. Most patients have some initial shortness of breath because of irritation of the diaphragm and wound pain. Some will go on to develop some fluid around the lung that may require drainage.

- Wound infection. Because of the immunosuppressive medicines and the major surgery wound infection is not uncommon. It usually is easily managed on the ward

- Rejection. Acute rejection occurs in around 1/3 of liver transplant patients. It is diagnosed by blood tests, and confirmed by biopsy. It is almost always treatable but requires a short re-visit to hospital.

- Infections. After transplant the immune system is dampened to help prevent rejection and this means there is a higher risk of infections of all types.

- Cancer. Transplant patients are at a higher risk of cancer development, because under normal conditions the immune system helps to fight cancer in the body.

FAQs

I have liver cancer, can I have a transplant?

Only those with small (< 5cm) hepatocellular cancers are considered for transplant. This is because larger or other types of cancer have an unacceptably high risk of returning in an aggressive way after transplant.

Will I be able to eat normally afterwards?

Yes, there are no dietary restrictions.

I have hepatitis C, will it be cured by transplant?

No, unlike hepatitis B where there are extremely effective treatments available, hepatitis C will not be cured by transplant. Instead, the cirrhotic burnt out liver will be replaced by a fresh one. Unless a cure is found most patients with hepatitis C will see it affect the new liver, but hopefully only after many years. A small number, around 5%, have a very aggressive early type of recurrence of hepatitis C.

How long will I be on the waiting list?

Unfortunately some patients wait many months or years for a liver transplant.

What are my chances of surviving?

More than 90% of patients survive the first year and just under 80% are alive at 5 years.

Can I use a live donor?

At the moment we only offer this option for children recipients. In the future this may be available for adults as it is in other parts of the world.

I would like to register as a donor, what should I do?

Most importantly, tell your family your wishes. You can register on the Australian Organ Donor Register Tel. 1800 777 203 More information about organ donation can be found here

(www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcarticles.nsf/pages/Organ_Donor_Registry/)

For more information about liver transplant follow the information link on the Australian

Liver cancer

Information for Patients

Liver Cancer is classified into Primaries and Secondaries.

Primary Liver Cancer.

Primary Liver cancer is where the cancer arises from the cells within the liver. There are two main types, and a few other very rare types.

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Also known as hepatoma or HCC. This is the most common primary liver cancer. It arises from the main liver cells known as hepatocytes.

Predisposing factors

HCC is most commonly (90%) associated with chronic liver disease. Cirrhosis of the liver is usually present by the time a cancer grows. In these circumstances the cancer has grown as a result of repeated inflammation and repair within the liver.

The other 10% of HCC grow spontaneously or as a result of transformation from an adenoma (a benign growth). Some of these are called fibro-lamellar HCC because of their appearance.

HCC tends to start off growing quite slowly and as it gets bigger it gets more aggressive and can spread.

Diagnosis

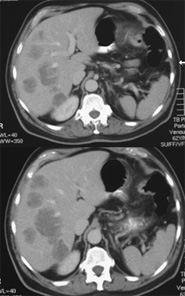

HCC is most commonly diagnosed in this country by a screening test performed on someone with cirrhosis. Often this will be a blood test (alpha-feto-protein) which becomes elevated in around 60% of patients with HCC. Other tests to detect HCC are Ultrasound and CT scans of the liver.

Once a tumour is identified, further tests are performed to determine the best treatment option. These tests may include CT scans, MRI scan, angiograms, portal venous wedge pressures, and biopsy of the non cancerous liver (to check for cirrhosis).

Biopsy of the liver tumour is rarely required and may cause bleeding or spread of the cancer. Biopsy of the tumour should only be performed if the cancer is felt to be incurable by either liver resection or transplant.

Prognosis

The prognosis (expected outcome) with HCC varies greatly according to the size and number of the cancers, whether there has been any invasion into veins, and whether there has been any spread. The prognosis is also affected by the degree, if any, of cirrhosis.

Treatment  Surgery (Liver Resection). The best treatment for HCC is the complete removal of the tumour. This is only possible in around 15% of those found to have HCC because; the tumour has already spread, or is in a vital area of the liver that can’t be removed, or because the cirrhosis is so advanced that surgery is too dangerous. Liver resection will cure up to 40% of patients operated on, with much of the recurrence after surgery being the growth of new cancers in a diseased liver.

Surgery (Liver Resection). The best treatment for HCC is the complete removal of the tumour. This is only possible in around 15% of those found to have HCC because; the tumour has already spread, or is in a vital area of the liver that can’t be removed, or because the cirrhosis is so advanced that surgery is too dangerous. Liver resection will cure up to 40% of patients operated on, with much of the recurrence after surgery being the growth of new cancers in a diseased liver.- Liver Transplant. Liver transplant is suitable for some patients with small HCCs where the cirrhosis makes it too dangerous to remove the tumour with resection. Liver transplant can cure up to 70% of highly selected patients.

- Local Ablation. There are numerous techniques now available to kill off small HCCs without removing them. These include Radio-Frequency-Ablation (RFA), Cryotherapy, Alcohol or Ascetic Acid injection. These treatments are all limited to the treatment of relatively small HCCs (generally <4cm diameter).

- Trans-Arterial Chemo-Embolisation (TACE). Chemotherapy as a pill or in a vein is not very effective against HCC. However, high dose chemotherapy delivered directly to a cancer via the artery to the liver can be effective at shrinking HCC, and is frequently used for larger tumours.

- Iodine131 Lipiodol. This is a radioactive substance that can be injected into the artery supplying the liver and ‘homes in’ on HCC to deliver a concentrated radiotherapy effect while sparing the remainder of the liver. It has effects similar to TACE.

- Cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma is the other main liver cancer primary and is a tumour of the bile ducts cells. It can occur near the main ducts just beyond the liver or deep in the liver itself.

Predisposing factors

Patients suffering with chronic inflammatory conditions of the bile ducts such as the rare disorder of Primary Schlerosing Cholangitis, are at a higher risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma. Oftentimes, however, there is no clear predisposing factor evident, although, like nearly all cancers, advancing age is often present.

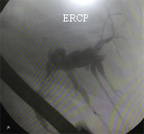

Diagnosis Cholangiocarcinoma may present as either a lump seen on CT scan or because it has caused blockage of the bile duct leading to jaundice (yellow colouring). Weight loss, poor appetite and nausea may be present. Investigations to confirm the diagnosis include CT scans, Ultrasound, MRI scans, Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography (ERCP), and blood tests.

Cholangiocarcinoma may present as either a lump seen on CT scan or because it has caused blockage of the bile duct leading to jaundice (yellow colouring). Weight loss, poor appetite and nausea may be present. Investigations to confirm the diagnosis include CT scans, Ultrasound, MRI scans, Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography (ERCP), and blood tests.

A needle biopsy is not usually required and may cause spread of the tumour.

Prognosis

The prognosis (expected outcome) with cholangiocarcinoma varies greatly according to the size and position of the cancer, whether there has been any invasion into veins, and whether there has been any spread. The prognosis is also affected by the state of the liver; the degree if any of cirrhosis.

Treatment - Surgery (Liver Resection). The best treatment for cholangiocarcinoma is the complete removal of the tumour. The ability to remove it depends on the presence of spread and the position of the tumour. It is often necessary to remove a large part of the liver if the tumour arises at the point where the left and right bile ducts merge (Klatskin) tumour. Surgery to resect these tumours can be challenging and sometimes impossible.

- Chemotherapy. Some patients are suitable for chemotherapy, although chemotherapy alone would not be expected to cure this cancer.

- Radiotherapy. External beam radiotherapy can help to shrink tumours that are causing symptoms, but is not curative in this cancer.

- Stenting. For cancers that are blocking the bile duct, and causing jaundice, plastic or metal tubes are often inserted to allow the flow of bile and to relieve the jaundice.

Secondary Liver Cancer

Secondary (Metastatic) liver cancer is where the cancer started elsewhere in the body and spread to the liver. The liver is a very common spot for secondaries to occur. Only liver secondaries that are suitable for surgery are discussed here. Just about any cancer can spread to the liver in late stages.

Colorectal Metastases

The most common treatable liver secondaries are from the rectum or colon (the large bowel). The blood from the bowel runs via the mesenteric and portal veins into the liver, so it is no surprise that the liver is a common site of secondaries from bowel cancer.

Up to 70% of patients with colon or rectal cancer will develop liver secondaries. Around 1/3 of these will have their secondaries confined to the liver, and around 1/3 of those will have removable cancers (resectable disease).

Diagnosis Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in the liver might be present at the time of bowel surgery, or show up months or years later. It might be diagnosed during the original surgery or be found using screening tests following successful bowel surgery. Occasionally the liver secondary is diagnosed before the bowel tumour is apparent. The common screening tests used are a blood test (CEA), and ultrasound or CT scans. Once a liver metastasis has been found it is crucial to work out whether it is alone or there are others. If there are others it is important to know whether they are only in the liver or whether there is cancer elsewhere. To help work this out patients have CT scans, chest x-ray, blood tests and a PET scan.

Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in the liver might be present at the time of bowel surgery, or show up months or years later. It might be diagnosed during the original surgery or be found using screening tests following successful bowel surgery. Occasionally the liver secondary is diagnosed before the bowel tumour is apparent. The common screening tests used are a blood test (CEA), and ultrasound or CT scans. Once a liver metastasis has been found it is crucial to work out whether it is alone or there are others. If there are others it is important to know whether they are only in the liver or whether there is cancer elsewhere. To help work this out patients have CT scans, chest x-ray, blood tests and a PET scan.

The PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan is a nuclear scan that relies on an injection of radioactive sugar. Since cancers rely on sugar for their energy and use it more rapidly than normal tissues, the radioactivity accumulates in the cancers, and shows up as a ‘hot spot’ on the scan. The PET scan can diagnose tumours as small as 1cm. Recent evidence shows that patients who undergo liver surgery for colorectal secondaries, who have otherwise negative PET scans, do very well.

Biopsy of the tumour is rarely required and should not be performed if the tumour is resectable.

Prognosis

The prognosis (expected outcome) with colorectal cancer metastases varies according to resectability. For patients with removable tumours, the long-term (5 year) survival is around 40%. For those with widespread disease, long-term survival is limited, but chemotherapy when suitable is likely to prolong life.

Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer are best looked after with a multi-disciplinary team approach that includes specialist surgeons, oncologists and nurses.

Treatment

- Surgery (Liver Resection). The best treatment for liver secondaries due to colorectal cancer is the complete removal of the tumour(s). The ability to remove the tumours depends on their position, number and whether there is spread outside the liver. Up to 70% of the liver can be removed to clear the cancer.

- Chemotherapy. Some patients are suitable for chemotherapy, although chemotherapy alone will not cure colorectal metastases. Chemotherapy has a role in shrinking tumours and extending life. There is emerging data about surgery following (Neo-Adjuvant) chemotherapy, where the chemotherapy has shrunk a previously un-resectable tumour down to a resectable one. (Adjuvant) Chemotherapy is usually recommended after successful surgery to ‘mop up’ any small tumour deposits that might be undetected.

- Other treatments. There is thus far little convincing evidence for other treatments for liver secondaries from colorectal cancer.

Non-Colorectal Metastases

Many other tumours spread to the liver. Liver resection is sometimes appropriate for neuroendocrine, renal, melanoma and some sarcomas. Resection for other secondaries is not usually indicated.

Liver Resection

Information for Patients

The Liver The liver is a large organ in the upper abdomen, just below the diaphragm. It is a major source of proteins for the body and processes much of the food we eat. It also secretes bile via the bile ducts into the gut. The gallbladder (D) stores bile. It is connected to the main bile duct (A) and hangs off the liver.

The liver is a large organ in the upper abdomen, just below the diaphragm. It is a major source of proteins for the body and processes much of the food we eat. It also secretes bile via the bile ducts into the gut. The gallbladder (D) stores bile. It is connected to the main bile duct (A) and hangs off the liver.

The liver receives blood from two sources; the portal vein (B) and the hepatic artery (C). Blood leaves the liver through hepatic veins (E) into the vena cava just below the diaphragm. The liver is divided into eight anatomical segments by the branches of its veins. This anatomy provides the basis for most resections of the liver.

Regeneration

The liver is able to regenerate its substance. This means that when part of the liver is removed, the volume of the remaining liver increases until it is close to the volume of the original whole liver. Bile ducts and blood vessels do not re-grow. In general up to 70% of a healthy liver can be removed, however, when there is chronic liver disease present, much less can be removed safely.

Why would the liver need resection?

The most common reason for liver resection is potentially curable cancer. The most common of these, in this country, is spread (secondaries) from a bowel cancer when there is no spread to other organs. The next most common is for hepatocellular carcinoma (Hepatoma, HCC). This is a cancer that originates in liver cells (primary), and is usually associated with chronic liver disease.

It is unusual to resect other cancers, although it is sometimes performed for cholangiocarcinoma (cancer of the bile duct), gallbladder cancer, and for secondaries from; neuroendocrine tumours (like carcinoid), renal cancer, melanoma, and rarely other cancers.

There are a number of benign lesions that can occur in the liver, most don’t cause any symptoms or problems and can be safely watched or left alone, however it is occasionally necessary to resect certain benign lesions including adenoma, cholangiohepatitis, and giant haemangiomas.

Sometimes it is not possible to be sure of a diagnosis before surgery even with modern imaging techniques. Biopsy of the liver is not routinely recommended because it has the potential to cause bleeding and spread cancers. Therefore, occasionally someone may have a resection for what turns out to be a benign condition because the suspicion for curable cancer was high.

What tests are done?

This very much depends on the history and examination. At a minimum, patients undergoing liver resection will have a CT scan (or sometimes MRI), and blood tests. If the tumour is thought to be a secondary from bowel cancer then a PET scan will be performed to rule out spread to other organs.

Other tests will frequently be required to rule out other tumours and assess resectability.

How is the liver resected?

There are two broad methods

- Open resection. This is the preferred method for major resections particularly if the tumour is close to a major blood vessel. It is also used for minor resections in difficult to access parts of the liver.

- Laparoscopic (keyhole). This is a newer method and uses a camera inserted into the abdominal cavity along with several other small cuts to introduce instruments. It is sometimes necessary to make a hole large enough to insert a hand into the abdomen to assist with safe resection (hand-assisted technique). The liver piece is removed through a small enlargement of one of the incisions.

With both methods, the principals are the same: The liver is mobilized. The vessels to the portion being resected are frequently tied. The parenchyma (meat) of the liver is then cut through using a variety of techniques. Care is taken to seal off the blood vessels and bile ducts that course through the liver. A normal rim of liver tissue is removed around the tumour to ensure ‘clear margins’.

The post-operative course

The post operative course is different for each person and differs greatly between open and laparoscopic surgery.

Most patients are admitted to Intensive Care or the High Dependency Unit for the first post operative night.

Those having laparoscopic surgery can expect to stay between 1 and 4 nights in hospital. Those having open surgery stay between 5 and 10 days on average.

Most patients will be able to take oral intake within 24hours of surgery.

Those having laparoscopic surgery should expect to take 2-3 weeks away from work.

Those having open surgery can expect 6-12 weeks away from work.

What are the potential complications?

The risks of different complications varies between patients. In general the larger the resection the higher risk. The risks are also higher if the patient is older, has significant other illnesses, or has chronic liver disease. Most patients have a fairly straightforward course, but some will have serious complications.

Potential complications of liver surgery include (but not limited to);

- Bile leak. Bile may leak from the cut surface of the liver into the plastic drain. Further procedures to correct the leak are sometimes required.

- Bleeding. Bleeding may occur during the surgery (requiring transfusion), or post operatively occasionally requiring a return to the operating room to control bleeding.

- Intra-abdominal collection. Fluid may accumulate near the liver (blood or bile) that can become infected and occasionally needs to be drained.

- Liver failure. When there is insufficient liver mass to function properly, jaundice and fluid accumulation may occur until regeneration of the liver occurs. If the failure progresses rapidly it can lead to post-operative death.

- Respiratory problems. Most patients have some initial shortness of breath because of irritation of the diaphragm and wound pain. Some will go on to develop some fluid around the lung that may require drainage.

- Wound infection.

- Clots.

- Allergic reaction.

- Heart trouble.

FAQs

Will I need chemotherapy afterwards?

That will determined by a medical oncologist (cancer specialist). Chemotherapy is usually recommended for those with bowel secondaries, and much less for other types of cancer of the liver. Those who have hepatocellular cancer are frequently suitable for an injection of radioactive lipiodol (this helps to prevent further cancer development).

Will I be able to eat normally afterwards?

Yes, once the liver has regenerated there are no dietary restrictions.

What are the chances of cure?

This depends on a number of factors and can often only be truly estimated after the resection and pathology examination of the tumour.

Will I need further check ups into the future?

Yes, it is generally advisable to have regular blood tests and scans for at least five years after a resection so that, if tumour is to recur, it can be diagnosed early.

Twitter

Twitter

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram

LinkedIn

LinkedIn